We associate this Upcounty favorite with summer outdoor fun–but that’s not what the lake’s creators had in mind when it was built.

It was just before the election in 1920 and several men were gathered informally at the Waters General Store in Germantown discussing the pros and cons of the various candidates. When it came up that a local citizen, John Bolton, was refusing to vote, one of the men, Guy Vernon Thompson, volunteered to try to persuade him to do his civic duty.

Burned down in the 1970s, Germantown Train Station was rebuilt to its 19th century splendor, the vision of a famous Baltimore architect.

Today, Germantown Train Station is used as a waiting room for commuters and has a coffee shop, Alafia Crossing, operated by Bota King. More than 800 passengers board the trains that leave the MARC (Maryland Area Regional Commuter) train in Germantown every weekday morning, a stop along the Brunswick Line that travels from West Virginia to Washington, DC.CSX Transportation owns this line of rail. But the tracks used to be part of a Baltimore & Ohio network dating back to the 19th century.

Germantown Train Station was built in 1891, replacing a smaller frame station built in 1878. The building consisted of two large waiting rooms heated by wood stoves and separated by a ticket office. There was a door connecting the two rooms on the inside, and both rooms also had doors to the outside on both the train track side and the road side. The ticket office had both an outside and an inside window for selling tickets.

Germantown’s station was a Ephraim Francis Baldwin (1837‑1916) design almost identical to the buildings in Kensington and Dickerson. In fact, nearly all of the station houses on the Metropolitan Branch of the B & O Railroad were designed by the famous Baltimore architect.

Baldwin is most recognized for the large Victorian gothic style station at Point‑of‑Rocks, MD, built in 1875. His small, one‑ and two‑room station houses were also very significant architecturally. The original station houses at Rockville,

Kensington, Gaithersburg, Dickerson and Point of Rocks still stand and are all county historic sites. Vandals burned down the Germantown station in 1978.

Montgomery County rebuilt Germantown train station with the help of federal funding in 1987. The station was reconstruction on its original site and with the original plans of Francis Baldwin, which were archived at the B & O Railroad Historical Society. But there are some differences: There’s only a single room on the inside and a punch-out addition on the east side, thicker boards were used for the trim, and the “Germantown” name board was placed on the building rather than from the eave.

The waiting sheds built in 1997 are taken from original designs for waiting sheds and milk platforms made for the B & O Railroad in 1906, which were also archived at the B & O Railroad Historical Society.

For more information see The Met: a History of the Metropolitan branch of the B & O Railroad available at the Germantown Historical Society at www.germantownmdhistory.org or email [email protected]. Susan Soderberg is president of the Germantown Historical Society.

The peace of the little village of Germantown was broken by the sound of gunshots on January 20, 1932. Robbers had entered Horace Waters’ store at around 7 p.m. They shot and killed Mr. Waters, a prominent citizen of Montgomery County, and wounded his clerk

Horace Waters was known to carry a large amount of cash, and often loaned money to local people in need, both white and black. He operated a general store in Germantown at the corner of Germantown Road and Clopper Road for more than 50 years. A grandson of one of the first settlers of the area, William Waters, Horace was a director of the Farmer’s Banking and Trust Company of Rockville and well respected in the community.

On the evening of January 20, 1932, Mr. Waters was sitting behind his desk at the rear of the store, and his clerk, Richard Bennett, was at the counter in the front. Three local men, Herman Moore, Milton Warren, and Quaint Perry were sitting around the stove near the back. Three men entered the front door of the store and went directly to the rear where the leading man pointed a gun at Mr. Waters and demanded money. Waters resisted when the robber started to go through his pockets and the robber shot him in the chest just under the heart. He died almost immediately.

On seeing the scuffle, Mr. Bennett had rushed to the aid of his employer, only to be shot in the wrist by the assailant, which bullet also hit Mr. Waters in the hip.

Just then there was the sound of a vehicle pulling up to the front door and, frightened of being caught, the three intruders hurriedly left.

The vehicle was a bread truck pulling up to get gas. J.M. Siever and W.C. Hershberger got out of the truck and entered the store. When they came upon the scene Hershberger immediately telephoned the police. It was found later that Mr. Waters still had his wallet pinned inside his coat with more than $100 in it.

The police combed the area but found no trace of the three bandits. The three men who were inside the store during the incident, and Bud Praither who an informant said was a person that the robbers were looking for were jailed and questioned, but released after a few days.

State’s Attorney Stedman Prescott assigned the case to Gen. Gaither, Police Commissioner for Baltimore City, but they got no further than the local police in solving the case, even with Montgomery County offering a $1,000 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the killers.

In April, however, the case was revived when Mary Burns, wife of the local postman Harry Burns found a gun under the hedge in front of her house at 19311 Germantown Road (now Liberty Mill Road), the probable escape route of the robbers. The gun was a 45 caliber pistol, the same that shot Horace Waters, but no fingerprints were found on it.

The murder was not solved until four years later.

According to an article written by Jack Toomey for the Monocacy Chronicle in 2007, the murderer, Donald Parker, was overheard telling a fellow inmate at the penitentiary in Baltimore about the killing in 1936. He was tried and convicted of the murder and sentenced to life imprisonment.

According to police files, Parker, Gordon Dent and James Gross made up a gang who held up filling stations, taverns and stores all around the mid-Atlantic area. Dent and Gross had already been hanged for another murder by that time. According to Toomey, Parker was released on parole in 1953, re-arrested in 1958, paroled again in 1962 and died in Washington, D.C. in 1973.

The funeral of Horace D. Waters was attended by about 500 people. Canon Arthur B. Rudd of the Washington Cathedral officiated. He is buried at the Neelsville Presbyterian Church Cemetery. He was 79 years old when he was killed and left a widow, Valeria Dorsey Waters, and five adult children.

The store clerk who was wounded, Richard Allen Bennett, age 68 at the time, went on to live another 14 years. He is also buried at the Neelsville Presbyterian Church Cemetery.

A Sunoco gas station now occupies the site of the Waters General Store at the northeast corner of Clopper Road and Liberty Mill Road.

Written by Susan Soderberg, President of the Germantown Historical Society.

Today we call all places where people are buried cemeteries, but it is actually a fairly recent term that first appeared in America in the 1830s with the first corporate Memorial Parks. Before that there were burial grounds—municipal burial grounds, churchyard burial grounds and family burial grounds. Burial grounds are sacred places. They mark where our ancestors lie, commemorate the special, and memorialize the unique, but they are also primary sources that can tell us about birth and death dates, where a person lived, who was related to whom, and social customs surrounding death and burial.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, when Montgomery County was still frontier or at least very rural, people died they were buried on thier property when they died. Almost every farm had its own burial ground. In towns and urban areas, the dead were buried on church or town property in churchyards or graveyards. As cities and towns grew, these places for the dead grew overcrowded and at the same time people began to realize that decaying matter spread disease. So, the burial grounds had to move outside the city. Official Cemeteries were established outside cities and towns beginning in the 1830s. These were either voluntary associations or private, often for-profit, corporations. The organization would purchase the land then sell burial plots, keeping a trust fund for future upkeep. Sometimes these cemeteries were created as parks, landscaped with exotic trees and flowers and having wandering paths, benches and gazebos creating a pastoral atmosphere for the “contemplation of death and life.” Lovers strolled and families picnicked in these park cemeteries.

As family farms were sold and older members went to their own rest in one of the new cemeteries, many family burial grounds were lost to the ravages of nature, or, sometimes, to the bulldozer. With all of the development in Germantown we have lost many of our small family burial grounds and all of the slave burial grounds. Currently we have four church burial grounds, one modern cemetery, and five existing family burial grounds within the Germantown Planning Area.

Many of the older tombstones have artful sculptures, symbols and interesting verses. Some of the more common symbols from the Victorian era are: rose for purity; rosebud or lamb for innocence often found on the stone of a baby or child; oak leaf for remembrance, laurel branch for honor. Metal medallions mark the graves of veterans, a different one for each war.

Historic Burial Sites in Germantown

The oldest church cemetery, and also the largest, is Trinity Presbyterian at Rt. 355 and Neelsville Church Road. It contains more than 500 graves, the oldest dating to 1849. The most famous person buried here is Guy Vernon Thompson, the last man hanged in Montgomery County. He was convicted of killing a man and his two step-children with dynamite in 1923 in Germantown. Also buried here is Hartman Richter, cousin of Lincoln Assassination conspirator George Adzerodt, who unknowing harbored the fugitive and in whose home he was arrested.

The Germantown Baptist Cemetery at Riffleford Road and Germantown Road dates back to 1881 and has more than 100 graves. The mausoleum of Eldridge Bowman and his wife dominates the churchyard. Eldridge was one of three brothers who built the mill next to the railroad station in Germantown. You can also find the grave of Nathan Page, one of the men responsible for the capture of George Atzerodt, and the plot of the Metz family, also involved in the Atzerodt story.

The Trinity Methodist Cemetery at the northwest corner of Rt. 118 and Clopper Road holds about a dozen graves and dates back to when the Church was formed in the 1860s. The church split into a Northern Church and a Southern Church after the Civil War, and each built its own church in Germantown in 1902. The old church was abandoned and the site is now under Germantown Road. The Methodist Cemetery is now overgrown with brambles and weeds and is inaccessible except by walking through the football field behind the Germantown Recreation Center.

The grounds of the Asbury Methodist Cemetery on Black Rock Road are well kept, but many of the tombstones are fallen over or missing. It most likely contains more than 100 graves. Some of the earlier graves were only marked with an upright field stone, now fallen over. The first church here was built in the 1870s by the African-American community of Brownstown, named for William Brown who donated the land for the cemetery. This church burned in the 1950s and was rebuilt by the congregation.

Two of family burial grounds in Germantown have been preserved and their upkeep is included in the homeowners association covenant, thanks to the efforts of the Germantown Historical Society.

The Basil Waters burial ground is next to 12509 Hawks Nest Lane in Milestone. Here you will find the remains of the Waters family who lived in the house Pleasant Fields on Milestone Manor Lane. Here you will find the graves of Anne Magruder Waters and her son Robert, age 9, and her daughter Susannah, age 18, who all died within days of each other in a Black Measles epidemic in 1824.

The Mobley/Magers/Arnold burial ground is next to 18633 Village Fountain Drive in Fountain Hills. This graveyard is surrounded by a metal fence and contains a few tombstones, but the two dozen or more graves extended beyond this fenced area before the bulldozers came in. Many of the graves were marked only by upright fieldstones in rows.

Many family burial grounds in Germantown are in need of care. If you are interested in helped, please contact the Germantown Historical Society. For more on the history of cemeteries: The Last Great Necessity: Cemeteries in American History by Charles David Sloane.

Susan Soderberg is the president of the Germantown Historical Society.

By Susan Soderberg of the Germantown Historical Society

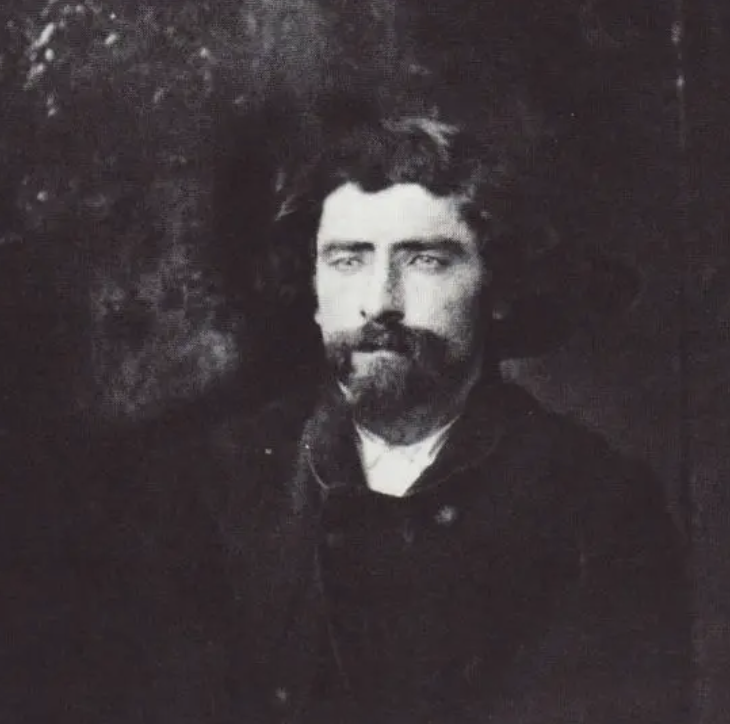

It was just before the election in 1920 and several men were gathered informally at the Waters General Store in Germantown discussing the pros and cons of the various candidates. When it came up that a local citizen, John Bolton, was refusing to vote, one of the men, Guy Vernon Thompson, volunteered to try to persuade him to do his civic duty.

What was not known to the others was that Thompson had more on his mind than the election. He had a suspicion that Bolton was having an affair with his wife. When he knocked on the door of the miller’s house for the Waters Mill where Bolton was living, Bolton refused to let him in and told him to go away.

Thompson continued to bang on the door until Bolton came out and threatened him with his shotgun. Thompson tried to wrestle the gun away and in the ensuing struggle Thompson was shot in the shoulder – a wound requiring medical attention, but no serious damage. The police did not arrest Bolton since he was protecting his home and family, but did confiscate his shotgun.

Act two of this drama is gathered from police evidence, the testimony of the surviving victim, Thompson’s own admissions, and the testimony of his wife and others against him at the trial. Thompson’s wife, Hester, said that he had left the house about 1:00 a.m. on Nov. 18 and came back with dynamite, then gone out again, not returning until after 4:00 a.m. Thompson had stolen the keys to the Waters & Thrift General Store warehouse, broken in and taken the dynamite. His fingerprints were found on a new plow in the warehouse and his footprints were found outside.

Thompson had crept up to the Bolton house while the inhabitants were sleeping and blown it up, killing John Bolton, and the two childrenof Bolton’s housekeeper, Hattie Shipley: Harold, age 3, and Evelyn, age 5. Hattie was the only survivor. According to her account: “I had just gotten up to look at the clock and it was fifteen or twenty minutes after 4 o’clock. I went back to bed and was just dozing off when there was a tremendous flash and explosion. I saw the flash and heard the noise.

Then I was stunned for a minute, and after picking myself up across the room where I had been thrown, I heard Mr. Bolton groaning- ‘My God. My God. Hattie do something for me or I will bleed to death.’ I went to him and felt his head and it was all bloody. Then I heard my baby girl strangling as though she could not breathe. I went to her, I lifted a beam from my little girl’s throat so she could breathe, I don’t know what happened to my little boy.”

Evelyn died during the night, Harold had been killed instantly, and John Bolton was taken to the hospital, but died the next day from internal injuries.Hattie stayed in the wrecked house until dawn, afraid that the person who had blown up the house might be lurking outside. Then, although wounded herself, she made her way to the Dorsey farm a half mile away.

Guy Vernon Thompson was convicted of the crime by a jury at the Montgomery County Courthouse on January 8, 1921 and was later hanged in the County jail yard (where the Montgomery County Council Building is today). He has the additional notoriety of being the last person to be executed by Montgomery County, that perogative passing on the state thereafter. The rope that he was hanged by is at the Montgomery County Historical Society.

The foundation of the Waters Mill millers house (the house that was blown up) is in Black Hill Park where the “Hard Rock Trail” crosses Lake Ridge Drive, about ¾ mile south of the entrance. The ruins of Waters Mill are on the Crystal Rock Trail, about a half mile from Crystal Rock Drive. The location of the Waters Store was across from the Germantown Train Station between the Bank and the Barber Shop.

Note: Margaret Coleman contributed to this story.

For more information about the History of Germantown, visit the Germantown Historical Society at the Historic Germantown Bank 19320 Mateny Hill Rd., Germantown (across from the MARC Train Station) or visit www.germantownmdhistory.org.

Metrobus leads in Covid performance rebound

Per WMATA: Metro ridership is outpacing projections through the first three quarters of fiscal year 2022 by nearly 40 percent. Through March, ridership has exceeded the initial forecast by 28 million passenger trips as more people chose bus and rail for travel throughout the region. Metrobus leads the way, accounting for 60 percent of overall Metro ridership, compared to about 40 percent for rail.

People returning to offices, higher gas prices, the return of large-scale events, and robust tourism are driving the resurgence. Ridership more than doubled as of March. Parking usage has tripled over the same period.

“These numbers are encouraging and welcome news for our regional mobility and economy,” said Board Chair Paul C. Smedberg. “While the Board’s budget assumed conservative ridership forecasts in the interest of fiscal responsibility, we are delighted that people are returning to the system more often than expected.”

Following a slowdown in ridership recovery during the emergence of Covid variants, Metro ridership rebounded in March, boosted by businesses resuming in-person work, as well as visitors attending activities and events during cherry blossom season. Average weekday rail ridership peaked Tuesday through Thursday at 230,000 and bus at 280,000.

Ridership continued to trend up in April, reaching as high as 300,000 on Metrobus. During peak times the number of riders continued to climb, showing an uptick in SmartBenefits® usage. SmartBenefits users nearly tripled since January with a pandemic high of 66,000 riders.

“People returning to Metro reduces traffic, combats climate change, and delivers clients, customers and employees to federal workplaces and local businesses,” said General Manager and Chief Executive Officer Paul J. Wiedefeld. “As the region transitions out of the pandemic and our services continue to improve this summer, we expect more residents and visitors will choose Metro.”

The trend is positive news for Metro’s bottom line, improving the financial outlook for the fiscal year ending June 30. More riders also mean more revenue from advertisers looking to capitalize on Metro’s increasing customer base. Advertising revenue sold in the system has more than doubled and is $2 million ahead of last year’s budget. Revenue from advertising supports Metro operations.

While ridership is expected to remain below pre-Covid numbers as the region’s travel behaviors change, Metrobus has reached 61 percent of pre-pandemic ridership levels. The positive trends for bus and rail are expected to continue, as the Board-approved budget continues more frequent bus service through the next fiscal year and rail frequency improvements are anticipated in late summer with the restoration of the 7000-series railcars to the fleet.

By Susan Soderberg of the Germantown Historical Society

There is a street with a strange name off Crystal Rock Drive in Germantown — Kinster Drive. Just what or who was Kinster and why is there a street named for him?

Let’s start with the land beneath the street. Now occupied by townhouses, this land was owned by the Waters family — three brothers who inherited adjacent property from their father — in the 1790s. The land was bisected by Interstate-270 in the 1970s, but the northern portion was owned by Dr. William Waters in the 1890s. His son, Charles Waters, was very interested in race horses, though not the kind of race horses you’d see today at the Kentucky Derby and Preakness Stakes. The kind of racing popular at the time was harness racing.

Instead of running at a gallop carrying a rider, harness racing horses pull a light-weight, two-wheeled cart called a “sulky” with a driver. Instead of galloping, the horses must maintain a trot, where alternate corner legs move forward together, or a pace, where the two legs on the same side move together. Harness racing aficionados claim that this kind of racing requires much more strategy than a full-gallop race, and that the horse has to be smarter because he is only controlled by the reins and whip of the driver.

Harness racing first became popular in New England during the mid-19th century. Its popularity spread across the country, through county fairs where racetracks were built and much of the racing took place. The American horse breed for harness racing descends from a horse named Messenger who was imported from England in 1788. His lineage traces back to the Godolphin Arabian, the Darley Arabian and the Byerly Turk. The breed today, however, looks nothing like the Arabian, with its delicate lines and tapered muzzle. The horses are long-bodied, short-legged and very muscular, and have large unrefined heads.

Harness racing became so popular that it became an official breed in 1880, when the American Trotting Register adopted a set of rules establishing a standard of speed for the mile — 2 minutes, 30 seconds for a trotter; and 2 minutes, 25 seconds for a pacer. All of the standard-bred horses in America today trace their lineage back to Hambletonian 10, born in 1840. Hambletonian sired 1,335 offspring.

Now, back to Kinster. He was born (or foaled as they say in the horse world) in 1894 on the Waters Farm, Pleasant Fields. He was owned by J.A. Smith and was sold as a yearling to Charles Waters for $24. Although the horse was called “unpromising” by those “in the know,” Waters knew that with Kinsman Wilkes as his sire (father), and Cress, as his dam (mother), he could very well be a winner, because both parents had produced winners before. As a matter of fact, Kinsman Wilkes would also be the sire of Dan Patch, probably the most famous trotter of all time.

Kinster’s chance came in September 1897 at the Montgomery County Fair in Rockville. His usual driver was unavailable and Thomas Cannon of Reidsville, N. C., took the reins and guided the stallion to win the race with a time of 2 minutes, 27 seconds, a record for the Fair. The next year he won the race at Baltimore’s Prospect Park with a time of 2 minutes, 16. 5 seconds, which “fairly dazzled the light harness world,” according to the Montgomery County Sentinel newspaper. The article went on to say:

“Kinster is the fastest trotter ever bred in this county or in all this section of country, and may truly be said to be one of the phenomenas [sic] of this phenomenal season of trotting and pacing.”

Kinster was a bay horse 15 hands high, with white stockings above his two rear hooves. He went on to win more races, ending his career with a record time of 2 minutes, 14.5 seconds. He then became a money-making stud horse at the Pleasant Fields Farm. One of the fillies he sired, Kinstress, was bred at the farm and sold for $3,500, the most money ever paid for a horse in Montgomery County at the time. She went on to beat her father’s best time by a quarter of a second.

Photo courtesy of the Germantown Historical Society

The Lincoln Assassination Connection, by Susan Soderberg

Many of you who have seen the recent movie The Conspirator will know that George Andrew Atzerodt (alias Andrew Atwood), was one of the Lincoln assassination conspirators executed on July 7, 1865. Atzerodt was arrested in Germantown, the town where he had spent many years as a boy. How he got involved with the Booth gang and why he ended up back in Germantown is a compelling story.

This story begins in 1844 when Atzerodt, age 9, arrives in Germantown with his family, immigrants from Prussia. His father, Henry Atzerodt, purchased land with his brother-in-law, Johann Richter, and together they built a house on Schaeffer Road. In the mid-1850s, Henry sold his interest in the farm and moved to Westmoreland County, Va., where he operated a blacksmith shop until his untimely death around 1858. At this time Atzerodt and his brother John opened a carriage painting business in Port Tobacco, Md.

After the Civil War broke out the carriage painting business was not doing well, so John went up to Baltimore and got employment as a detective with the State Provost Marshal’s office. Atzerodt stayed on at Port Tobacco, but his main business was not painting carriages, it was blockade running and smuggling across the Potomac River.

It was on one of these clandestine trips that he met John Surratt, son of Mary Surratt, who was acting as a courier for Confederate mail. In November 1864 Surratt convinced Atzerodt to join the group, led by John Wilkes Booth, planning to capture President Lincoln, take him to the South and hold him for ransom. Since they planned to take their hostage through Southern Maryland and across the Potomac River, Atzerodt’s knowledge of the land and the river was indispensible.

Surratt took him to Washington where he met John Wilkes Booth and other conspirators. One plan to kidnap Lincoln on his way to the Veterans Hospital on March 17, 1865 failed when the President changed his plans at the last moment. The surrender of General Lee, however, had convinced Booth that more drastic measures were needed. The plan he presented was to immobilize the federal government by removing the top three heads. Booth would assassinate Lincoln, Lewis Powell would take care of the Secretary of State William Seward, and Atzerodt’s assignment was to kill Vice President Andrew Johnson.

Atzerodt’s courage evaporated when the time came, however, and he spent the evening drinking and wandering around Washington. In his confession he would claim that he never intended to kill the vice president and that he threw away the knife and pawned the gun that were given to him. Yet he did accept the knife and gun, and he did not turn in the other conspirators when he knew that the plan had changed from kidnapping to murder. These two things were what convinced the Military Commission that he should be executed.

After he heard that Booth had actually carried out his part in the plot, Atzerodt decided that he should leave Washington as soon as possible, and not in the direction of his home in Port Tobacco since that is where he knew Booth had gone. He would go to a place where he had friends and family, where they would welcome him without questions – his old home in Germantown. The following morning he managed to get through the blockade around Washington by buying the guards a few drinks. Then, catching a ride with William Gaither, he made his way to Gaithersburg and, after stopping for a drink at Mullican’s tavern, he proceeded on foot toward Germantown on the Barnesville Road (now Clopper Road). It was very late when he crossed the wooden bridge over Seneca Creek and saw a light in the Clopper Mill. He asked the miller, Robert Kinder, if he could stay the night, and Kinder, who knew Atzerodt from his previous visits to the area, showed him hospitality (for which he would later receive six weeks in jail).

In the morning Atzerodt started on his way to his cousin, Hartman Richter’s house just two miles away. He was very hungry, though, and, it being Easter Sunday, he decided to stop at the Metz home which was on his way. The family invited him to stay for dinner. The Leaman brothers, Somerset and James, were also visiting the Metz family. Of course, the assassination was the topic of conversation of the day, and Atzerodt must have let a few things slip to arouse the suspicion of the Leaman brothers who later testified against him. A neighbor, Nathan Page, was also at the Metz’s that day.

After dinner Atzerodt cut across the field to drop in on his cousin Hartman Richter, son of Johann. Knowing nothing of Atzerodt’s part in the assassination conspiracy, the Richters took him in and gave him a job on the farm. For the next three days Atzerodt did odd jobs at the Richter farm. On April 19, Atzerodt was sound asleep in an upstairs bedroom of the house. He was awakened at 5 a.m. by soldiers, one of whom was pointing a revolver at his head. He was quickly arrested and taken to Washington.

The soldiers, stationed in Clarksburg, had been alerted of a “suspicious character just up from Washington” by a tip from one of their local informants, James Purdom. Purdom had run into Nathan Page earlier and Page had told him about Atzerodt and what he had said at the Metz home. Purdom and Page would end up splitting the $25,000 reward for the capture of Atzerodt. Atzerodt was a goner anyway. A few hours after Atzerodt was arrested another group of soldiers arrived at the Richter home looking for him. This second posse had been sent by the Provost Marshal after receiving information from Atzerodt’s brother, John.

Hartman Richter, the Leaman brothers, as well as the old miller, were also arrested and imprisoned on a ship in Washington until the trial, after which they were released. Atzerodt was tried and convicted by a military court. He was hanged in the yard of the Arsenal in Washington along with Lewis Powell, David Herold and Mary Surratt.

The ruins of the Clopper Mill can be seen on the west side of Clopper Road just to the north of Seneca Creek opposite Waring Station Road. The home of Hartman Richter on Schaeffer Road in Germantown accidently burned down in 1982.

—

Much of the information on Atzerodt’s arrest came from the book, “Blood on the Moon: The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln,” by Edward Steers.

By Susan Soderberg of the Germantown Historical Society

When standing at the Germantown Library or BlackRock Center for the Arts, ever wonder what was there before Germantown Town Center was Germantown Town Center?

By Susan Soderberg

Families picnicking, children cavorting on the playgrounds, teens paddling around the lake in kayaks and fishermen dropping their lures hoping for a bite, summer is here at Black Regional Hill Park. Black Hill and Little Seneca Lake, forming the northern border of Germantown, is a well-used recreational area, especially on these hot summer days. But the lake was not created only for having fun. It is an emergency water supply for the Washington Suburban Sanitary Commission, the Washington Aqueduct, and the Fairfax County Water Authority in Virginia.

Little Seneca Lake is fed by the flow from Little Seneca Creek and its two main tributaries, Ten Mile Creek and Cabin Branch (“branch” being another word for stream). Native Americans used these waterways for fishing and had hunting camps in the surrounding hills. The first European settlers set up many mills along the fast-flowing streams. Farms were built and the little village of Ten Mile Creek had a school and Pyles grist and saw mill. After the train came through in 1873 people would come up from Washington in the summer to vacation in the country at several hotels in the area. One hotel on Ten Mile Creek that was not affected by the creation of the lake because of being situated on high ground is the 22-room High View Hotel, now a county historic site.

The story of the park and the lake goes way back to the 1960s when the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission (M-NCPPC) started buying up land around streams in Montgomery County to protect the watersheds and manage the resources of the county. Beginning in 1968, with the help of the Soil Conservation Service, the county surveyed the creeks and streams and developed a plan. The Seneca Creek watershed, and especially Ten Mile Creek were identified as particularly sensitive areas. A 1974 study of Ten Mile Creek showed that its species diversity was one of the highest of small steams in the county with three threatened species of fish: cutlips minnow, comely shiner and rosyside dace.

A Master Plan was developed for the Seneca Creek watershed in 1977, which included a multi-purpose reservoir. This coincided with a major water shortage in the Washington, DC-metropolitan area in the mid-1970s. So, in 1978 the county got together with the Washington Suburban Sanitary Commission (WSSC) and agreed to enlarge this lake and have it as an emergency water supply for the WSSC Potomac River intake. A steering committee was formed of engineers, environmental consultants, geo-technical consultants and government representatives to plan the park and lake.

After a plan was made it was presented to the public at a public hearing. After approval approximately 1,680 acres of land were acquired and the construction of the dam was begun. Twenty-one families were displaced, four dairy farms lost, Rt. 121 had to be redirected and a new bridge built over the forming lake. Of historic sites, one prehistoric site, a one-room schoolhouse and a log slave cabin were lost to the slowly inundating waters, as well as the home and farm of James Boyd, for whom the town of Boyds is named.

As to the benefits, besides an emergency water supply, Little Seneca Lake provides a recreational area, a warm water fishery, flood control, the reduction of sediment, and a new tax base of homes built near the lake to take advantage of the recreation and environment. In addition, the dam, completed in 1984, includes a cold-water release structure that allows water from several levels of the lake to be discharged into the spillway. Consequently, the temperature of the water can be regulated. Cold water coming from the bottom of the deep lake is released during the summer, allowing trout, seeded in the spring, to survive and grow. Wildlife abounds in the 2,000-acre park with beaver, deer, eagles, and many other kinds of birds and waterfowl.

The surface area of the lake is 505 acres and it can be as deep as 68 feet and it holds about 4.5 billion gallons of water. The lake is stocked for recreational fishing. Fish species found in the lake include largemouth bass, tiger muskie, channel catfish, sunfish, and crappie.

The emergency water supply has only been used once since the Lake was created. That was in the summer during the drought of 1999. Hopefully, it will not be needed again in the near future. The Lake and Park provide a wonderful place to escape the summer heat and have a good time, and this will last well into the future.