Clarence Kettler asked his brothers Milton and Charles to help him build Montgomery Village. Together, they created Kettler Brothers, Incorporated. The Kettlers’ vision for a “new town” was loosely based on the corridor cities concept envisioned in Montgomery County’s General Plan. The new town movement started in the United States after World War II and was, in some instances, a response and a remedy to overcrowding and congestion in urban areas. New towns were synonymous with “planned communities” – places that were carefully, purposefully designed from inception, usually constructed in previously undeveloped areas, with an effort toward being self-sufficient. The Washington region is home to two of the most famous planned communities in the country – Reston, Virginia, and Columbia, Maryland.

In the 1960s, the Kettler Brothers started buying farmland in the Gaithersburg area and eventually assembled more than 1,500 acres. In 1962, the Kettlers purchased the 412-acre Walker Farm adjacent to the City of Gaithersburg. This farm was their largest single property acquisition and where Montgomery Village started. Like many developers, the Kettlers named many new subdivisions in the sprawling “village” after the original farms: Walker, Thomas, Brothers Mill, French, Patton, Fulks, and Wilson. The Walker farm was developed into numerous residential communities – Walkers Choice, Cider Mill, Dockside – as well as a library, a day care center, South Valley Park, and the Montgomery Village Plaza retail center. In addition to memorializing the former farms, the Kettlers attempted to instill a sense of community identity in the names; for example, the “choice” in Walker’s Choice was meant to convey that this was a rental community; some units have since become condominiums. Stedwick means “the meadow,” or “the land that was a dairy farm.”

Watkins Mill Road was named after the Watkins family and the grist mill they operated in the area. The Kettler Brothers’ vision was to create attractive and desirable residential neighborhoods with a range of housing choices and plenty of green space and recreational opportunities, including parks, recreation centers, swimming pools, trails, and lakes. In creating a new community, the Kettlers were able to systematically plan where and how uses would interplay and function together. Locally serving retail centers were conveniently located throughout the area, along with several small office clusters and community facilities. The Village Center was planned to function as the town’s hub, a central location for shopping and community interaction. Other retail centers were located in the lower Village along Lost Knife Road and in the upper Village along Goshen Road.

Vehicular access in Montgomery Village was organized hierarchically with Montgomery Village Avenue serving as the north-south “main street.” Watkins Mill Road, along the west side of the Village, provides another north-south connector. Secondary roads such as Stedwick, Centerway, Apple Ridge, Arrowhead, and Wightman provide east- west connections. Secondary roads connect to smaller residential streets organized in a quintessential suburban pattern featuring curvilinear designs with numerous small private courts and cul-de-sacs. The Kettlers relied on the flexibility of a private street system to accommodate traffic. Houses were clustered close to the street to save space in the rear of the homes for private yards and, in some areas, to allow room for the Village’s network of public trails.

Lake Whetstone is situated along the eastern edge of lower Montgomery Village Avenue. The lake was created by a dam and is a focal landmark feature that provides a serene and peaceful panorama. The Kettlers felt so strongly about creating views of Lake Whetstone, they elevated the southbound lanes of Montgomery Village Avenue so drivers, walkers, and bikers going in both directions could take in the scenery. Lake Whetstone opened for boating and fishing in 1967. Montgomery Village also has Lake Marion and North Creek Lake.

Creating visually appealing neighborhoods was important to the Kettlers, but since much of the land they assembled had been farmed, there were few trees. The Kettlers wanted the new neighborhoods to have plenty of foliage and greenery; they moved fully grown trees into the new subdivisions so it appeared that the trees were original features of the landscape. With a special machine, the Kettlers brought in 10,000 fully grown pin oak trees and planted them in Whetstone and Stedwick and along Montgomery Village Avenue. Today, the Village’s neighborhoods are set among an abundance of mature, stately trees, and slightly rolling hills.

Montgomery Village’s housing types include apartments, condominiums, townhouses, single-family homes, and

a senior assisted living facility. Such a diverse spectrum of housing options- from rentals, to townhouses, to the large homes fronting Lake Whetstone- was unique among residential developments in the 1960s. When the Kettlers began building, residential condominiums were not common and townhouses were often referred to as row houses, which were common in cities, but not yet very familiar to suburbanites. The Kettlers pioneered the “back-to-back townhome” in the Village as an affordable housing option, available at a lower cost for first-time purchasers. The pattern of residential development is denser in the lower Village near existing, established, and more urban areas. As development proceeds to the north, it is less dense, characterized by townhomes and single-family residences in the upper Village adjacent to the County’s Agricultural Reserve.

Photo and information provided by Montgomery Planning.

Back in July of 2021 it was announced that the Montgomery County Green Bank and Sandy Spring Bank would be teaming up to provide flexible financing to help the Olney Ale House re-open.

We spoke with a representative from Montgomery County Green Bank in September, who let us know that the construction is moving along well and that construction could take around 3-5 months, but that is just an estimate. They said they want to make sure to keep the county up to date on potential activities around the reopening and would provide additional information soon. We have not heard any additional information since.

A kitchen fire at the Olney Ale House caused the restaurant to temporarily shut down in 2019 and COVID-19 only compounded the issues for the restaurant. As we wait for the reopening of the Olney Ale House, we wanted to share with you its history, courtesy of the Olney Ale House website.

In 1923, Richard Bentley Thomas and Ethel Farquhar Thomas purchased the five acre triangular shaped piece of property from the estate of Sam Owens. The property had a four room log cabin in the middle of what is today’s parking lot. The corner was known as Davis Corner.

Almost immediately construction began on a hipped-roof, pavilion-type building that would contain a kitchen, dining room and two bedrooms. This building was completed in 1924, and opened for business as “The Corner Cupboard.” They served homemade ice cream, breads, cookies, pies and cakes, as well as, sausage, scrapple and ham sandwiches from hams that were cured in their smokehouse. Garden vegetables were also grown and sold. The Corner Cupboard was a unique establishment and drew many loyal followers.

In 1930, a large addition was added to the original structure. This included bedrooms in the rear and a second floor with more sleeping quarters. At this time, heat was installed making it a year-round operation. The log cabin was torn down at this time.

1930 also saw the addition of the stone fireplace in the dining room. It was built by Adolphus Gordon. The rocks came from a factory building at Triadelphia. The left over rocks were used to build the bell tower at Sherwood High School.

Two famous visitors of this time were Herbert Hoover, perhaps visiting the area because of his Quaker background and Dean Acheson, who owned a summer home in the area.

In 1937, the business was sold and became the Francis Lattie Inn. Miss Lattie operated the business as a tea room and carried on many of the former owners’ traditions.

The business has changed hands many times and operated under a variety of different names. “The Anchorage” had a retired naval officer Harold Hilliard at the helm, a Maggie Levesque purchased it but little is remembered of her time, then Mrs. Cramer bought it and named it the “Country Corner Inn.”

In the late 50’s, Irma Turnbull purchased it, she kept it until 1962 and then sold it to the McKenzie’s. Mrs. McKenzie had been one of her waitresses. Both of these owners operated under the “Country Corner Inn.” Mr. McKenzie was an engineer at WTOP and when they remodeled the station he brought out the large windows that were being discarded from a sound booth. They are currently installed in the bar room.

Sometime in 1970, the Matney’s purchased it. They added what is now known as the Beer Garden. They operated as a steak house and sold liquor. Two years later, they sold it to George, Fred and Anita Virkus and the “Olney Ale House” was born.

In 2000, it was purchased by the current owners.

Among some of the reported famous visitors are Burl Ives, Eve Arden, Tyrone Powers, Talulla Bankhead, Harry and Bess Truman, Dwight Eisenhower, Milo O’Shea, Chris and Susan Sarandon and Jason Miller.

The following comes from PLACES from the PAST: The Tradition of Gardez Bien in Montgomery County, Maryland by Clare Lise Kelly (M-NCPPC)

Part 1 available here: Black History: African-Americans in MoCo Before the Civil War)

In 1870, the black population made up 36% of the total county population. After emancipation, many African-Americans were able to buy land from or were given land by white plantation owners, often their previous enslavers.

Free Blacks transformed fields and scrubland into intensively developed settlements of agricultural homesteads. Over 40 African-American communities have been identified in Montgomery County. Communities that are represented today by standing historic structures include, in the Poolesville area, Sugarland, Jerusalem, the Boyds settlement and the Martinsburg settlement; in the Potomac area, Tobytown, Pleasant View, Scotland, Gibson Grove, and Poplar Grove; Mt. Zion and the Sandy Spring settlement in the Olney area; Good Hope and Smithville, in the Eastern region; and Hawkins Lane, near Rock Creek.

The first community building constructed by residents was typically a church, often also used as a school and social meeting hall until other structures were built. A noteworthy complex of community buildings is found in Martinsburg, near Poolesville. Still standing are the Warren Methodist Episcopal Church (1903), Martinsburg School (1886), and the Loving Charity Hall (1914). The hall was the headquarters for a benefit society that provided health and burial services for families at a time when insurance companies did not allow coverage for black citizens.

Families built their own houses that typically had two rooms up and two rooms down. In the first years after emancipation, most houses were built of log. By the 1880s, blacks began to build frame houses, which ranged from simple one or two room structures to two story dwellings with two rooms on each level. While several community buildings from African- American settlements have been preserved, few houses built by free blacks have survived. Among the remaining examples are the John Henry Wims House (c1885) at 23311 Frederick Road, in the Clarksburg Historic District, and the Diggens House (c1870s-90s), 19701 White Grounds Road, in the Boyds Historic District.34

Quakers supported one of the earliest schools for black children, held in the Sharp Street Church about 1864. Sandy Spring area Quakers financed the school and supplied teachers from the nearby Friends’ school at Fair Hill. Public schools were not available to black children until after 1872.

The following comes from PLACES from the PAST: The Tradition of Gardez Bien in Montgomery County, Maryland by Clare Lise Kelly (M-NCPPC):

Though local tobacco plantations were small in scale compared to the large estates of the Deep South, they relied nonetheless on labor of enslaved people. In 1790, enslaved people were one-third the entire population in Montgomery County. The number of slaves exceeded that in Frederick County to the north (12%), but was not as large as its southern neighbor, Prince George’s County (52%). There were five times more slaves than free Blacks here in the 1840s-50s. The travesty of one person owning another and brutal treatment of enslaved people were realities of the county’s first 150 years.

Josiah Henson, an enslaved person in Montgomery County at the turn of the 1800s, described living conditions: “We lodged in log huts, and on the bare ground. Wooden floors were an unknown luxury. In a single room were huddled, like cattle, ten or a dozen persons, men, women, and chil- dren. All ideas of refinement and decency were, of course, out of the question. We had neither bedsteads, nor furniture of any description. Our beds were collections of straw and old rags, thrown down in the corners and boxed in with boards; a single blanket the only covering. The wind whistled and the rain and snow blew in through the cracks, and the damp earth soaked in the moisture till the floor was miry as a pigsty. Such were our houses. In these wretched hovels were we penned at night, and fed by day; here were the children born and the sick—neglected.” Henson’s memoirs inspired Harriet Beecher Stowe to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin. On Old Georgetown Road, the Riley House with attached log kitchen survives from the Riley plantation where Henson was enslaved for some 30 years.

Most plantations had much smaller populations of enslaved people than those found further south. Over half had five or less, and three quarters had nine or less. An exception was Allen Bowie Davis, who enslaved about 100 people in the 1850s. Quarters for enslaved people still stand at Davis’ Greenwood property, north of Brookeville. They are further discussed in the chapter on Outbuildings.

Members of Quaker and German communities opposed slavery. The Quaker community of Sandy Spring was home to the first freed slaves in the county. In the 1770s, Sandy Spring Quakers freed Blacks and conveyed land for a church and dwellings. The earliest black congregation in the county was established at Sharp Street United Methodist Church in 1822. Originally housed in a log building, the church was replaced in 1886 by a frame structure that burned in 1920. The present church was con- structed in 1923. In the western county, early free black settlements included Big Woods (1813) and Mount Ephraim (1814). Elijah Awkard of Big Woods was owner of one of the largest tracts of land (163 acres) for a black person in the late 1850s. In 1860, over 1,500 free Blacks lived in Montgomery County.

Vast numbers of fugitive enslaved people passed through Montgomery County on the Underground Railroad, an organized system of escape run by volunteers who sheltered, fed, and transported escaping slaves to destinations as far north as Canada. A primary factor behind the Underground Railroad was the supportive Quaker community which aided fugitives. Tradition holds that, among others, the enslavers of Sharon Bloomfield, and Mount Airy assisted runaway enslaved people.

We previously took a look at Clopper’s Mill, which was burned down by an arsonist in 1947- leaving ruins that are still visible off of Clopper Road in Germantown today. Seneca Creek was one of the main sources of power for the first 150 years of settlement in Montgomery County. Montgomery County has 44 mills

Below, we’ve compiled information from three sources to provide you with more information on the history of water mills in Montgomery County, specifically 19 mills that were found along Seneca Creek.

“A History of Early Water Mills in Montgomery County” by Eleanor M.V. Cook

“Mills on the Seneca and Their Tributaries” by Doris B. Cobb

“History of Western Maryland” by J. Thomas Scharf

Seneca Creek was almost the only source of power for the first 150 years of settlement. In 1795, Middlebrook Mills was up for sale and a selling point was Seneca Creek, described as “the most powerful consistent stream in the county”. Water power drove Grist mills, Saw mills, bellows for forges and Fulling mills.

Fulling mills dealt with processing woolen cloth. “In those days, home woven woolen cloth, as it came off the loom, was dirty and of loose weave. It needed fulling to remove the grease and compact the fibers before being useful as blankets or clothing.” “In a prolonged operation, the rough-woven cloth was soaked in a special solution of fuller’s earth, an absorbent clay which took nearly all the natural grease from the wool. The mill was used to pound the cloth by raising and letting fall a series of hammers as the cloth was moved and turned in soapy water.

Grist mills used a pair of millstones to grind grains such as buckwheat, rye and corn. There were two types of millstones. Country stones were quarried locally and used for coarse flour. Cullin stones, German millstones from Cologn and French Burrs(Buhrs), made of quartz, were used for fine wheat flour. A mill owner advertised, in 1795, that he had burrs. A fine example of a mill stone may be seen at the Clopper Mill ruins.

Montgomery County had 44 mills before 1800. Eight of them were on Seneca Creek and its tributaries. Perhaps the oldest was at Seneca Ford, near the mouth of Seneca Creek. It already existed by 1732.

By the 1840’s the land in Montgomery County had become worn out. New settlers were headed for the rich soils in Tennessee and Kentucky. It was only with the opening of the Baltimore and Ohio Rail Road and the introduction of the use of fertilizers that farming was reinvigorated. The use of lime, bone, phosphates and other fertilizers allowed significant increases in yields of wheat and Indian corn. In 1850, Montgomery County listed 51 mills; 6 flour, 25 grist, 15 saw, 1 bone, 2 clover, 1 paper, 1 sumac.

A survey of Seneca Creek mills has found nineteen mills along Seneca Creek and its tributaries:

- Seneca Ford (Tschiffely Mill) 1732 – 1931 on Seneca Creek

- Black Rock Mill 1815 – 1920’s on Great Seneca Creek

- Hoyles Mill ??? – 1893 on Little Seneca Creek

- Clopper Mill (Maccubbin’s Mill) ca. 1768 on Great Seneca Creek

- Long Draught Mill (Hutton’s Mill) pre 1850 on Long Draught Branch, a tributary of Great Seneca Creek

- Middlebrook Mills (Good Will Mills, Faw’s Mill) ca. 1795 on Great Seneca Creek

- Walker’s Mill 1877 – 1932 on Whetstone Branch, a tributary of Great Seneca Creek

- Watkins Mill ca. 1783 – 1908? on Great Seneca Creek

- Davis Mill ca. 1783 on Great Seneca Creek

- Ford’s Mill ca. 1825 on Wildcat Branch above Davis Mill

- Goshen Mill (Crow’s Mill, Riggs Mill) ca. 1774 – 1890 on Goshen Branch, a tributary to Great Seneca Creek

- Waters Mill ca. 1810 – 1895 on Little Seneca Creek

- Wolfs Cow (Darby Mill) ca. 1783 on Bucklodge Branch, which joins Little Seneca Creek to form Seneca Creek

- Lost Britches (Pyles Mill) ca. 1799 near a feeder stream to Ten Mile Creek which is a tributary to Little Seneca Creek

- Veirs Sawmill on Bucklodge Branch

- Magruder Sawmill on Great Seneca Creek

- Samuel Darby Mill (Oakland Grist and Sawmill) on Great Seneca Creek

- Dawson’s Mill on Dry Seneca Creek

- Midford Mill on Dry Seneca Creek

Grist mills continued to do a lively business into the early 1900’s grinding wheat. Montgomery County was once a highly intensive wheat growing region. Wheat was grown more intensively in central Maryland than anywhere else in the USA except Kansas and South Dakota. The milling business declined by WWI and few were in operation after 1925.

Featured photo shows Seneca Ford/Tschiffely Mill in 1916, courtesy of http://www.senecatrail.info/seneca.htm

Last April, Montgomery Parks opened the Josiah Henson Museum and Park, a 3.34-acre park located at 11420 Old Georgetown Road in the Luxmanor Community of North Bethesda. The museum and park is dedicated to telling the story of resilience and perseverance in overcoming slavery, based on the detailed words and experiences of Josiah Henson – enslaved in Montgomery County for much of his life.

The Josiah Henson Museum and Park tells the inspirational life story of Reverend Josiah Henson, who was born into slavery yet defied the odds to become an influential author, abolitionist, minister, public speaker, and a world-renowned figure. One of Henson’s many accomplishments was his 1849 autobiography, The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, which inspired Harriet Beecher Stowe’s landmark anti-slavery novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Who is Josiah Henson?

Josiah Henson was born on a farm near Port Tobacco, Charles County, Maryland, on a plantation owned by Francis Newman, in June of 1789. His father was enslaved by Francis Newman whereas Josiah Henson, his mother, and his siblings were enslaved by Dr. Josiah McPherson.

When Henson was a young boy, his father was punished for standing up to an overseer of enslaved people. He received a hundred lashes, and his right ear was nailed to the whipping post and then cut off. His father was sold away to Alabama. Josiah also experienced hardships and sufferings at the hands of his masters as well, including having his arms broken and several other injuries.

Following his family’s enslaver’s death, young Josiah was separated from his mother, brothers, and sisters. Henson’s siblings were sold first via auction. His mother was bought by Issac Riley of Montgomery County and when she pleaded to her new enslaver to purchase Josiah Henson, Riley responded by hitting and kicking her.

Josiah Henson was sold to Adam Robb of Rockville, Montgomery County. Adam Robb encountered Issac Riley and struck a deal, which resulted in Henson being sold to Riley and was reunited with his mother. Josiah Henson became very ill and his mother pleaded with enslaver, Isaac Riley, and Riley agreed to buy back Henson so she could at least have her youngest child with her, on the condition that he would work in the fields.

Henson rose in his enslaver’s esteem, and was eventually entrusted as the supervisor of his Riley’s farm, located in what is now considered North Bethesda in Montgomery County. In 1825, Riley fell onto economic hardship and was sued by a brother-in-law. Desperate, he begged Henson, with tears in his eyes, to promise to help him. Duty bound, Henson agreed. Riley then told him that he needed to take eighteen people which he enslaved to his brother in Kentucky by foot. They arrived in Davies County, Kentucky, in the middle of April 1825 at the plantation of Amos Riley.

In September 1828, Henson returned to Maryland in an attempt to buy his freedom from Issac Riley. He tried to buy his freedom by giving his master $350, which he had saved up, and a note promising a further $100. Riley, however, added an extra zero to the paper and changed the fee to $1,000. Cheated of his money, Henson returned to Kentucky and then escaped to Kent County, Upper Canada, in 1830, after learning that he might be sold again. In the last of these attempts to attain freedom, Amos Riley agreed to give Josiah his freedom in exchange for $300. Josiah raised the money only to find that his enslaver had raised the fee. Soon after, Henson learned that Riley planned to sell him in New Orleans, Louisiana, separating him from his wife and four children. When he found this out, Henson became determined to escape to Canada to gain his freedom. He took his family with him, including his wife and their children to start the new life northward

After convincing his wife to escape with him, Henson’s wife created a knapsack large enough to carry both of their smallest children; the eldest two would accompany his wife. The Henson family left Kentucky, traveling through the night, and sleeping in the woods throughout the day. They crossed into Indiana, then into Cincinnati. As the Henson family was crossing Hull’s Road in Ohio, Josiah’s wife fainted from exhaustion. As they continued on, they encountered Native Americans, and were reinvigorated with food and rest.

After crossing a lake in Ohio, Josiah encountered Captain Burnham, a ship captain, who agreed to transport the Henson family to Buffalo, New York; from there they would cross the river into Canada. Upon setting foot into Canada, Josiah Henson described the ecstatic feelings of liberation by throwing himself onto the ground and rejoicing with his family. On October 28, 1830, Josiah Henson became a liberated man.

Josiah Henson described the living conditions during his time being enslaved in Montgomery County at the turn of the 1800s:

“We lodged in log huts, and on the bare ground. Wooden floors were an unknown luxury. In a single room were huddled, like cattle, ten or a dozen persons, men, women, and chil- dren. All ideas of refinement and decency were, of course, out of the question. We had neither bedsteads, nor furniture of any description. Our beds were collections of straw and old rags, thrown down in the corners and boxed in with boards; a single blanket the only covering. The wind whistled and the rain and snow blew in through the cracks, and the damp earth soaked in the moisture till the floor was miry as a pigsty. Such were our houses. In these wretched hovels were we penned at night, and fed by day; here were the children born and the sick—neglected.”

If you’ve ever driven on Clopper Rd near Waring Station Rd in Germantown, you’ve likely seen the ruins of a building in the woods. That building is Clopper’s Mill, named for Francis C. Clopper, also the road’s namesake. Per the The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission:

Francis C. Clopper operated a mill on Great Seneca Creek. He expanded the existing stone mill in 1834 with bricks made at his Woodlands estate. The original mill dated from 1795, and a mill had been on site as early as the 1770s. Clopper’s Mill, now in ruins, stands near Clopper and Waring Station Roads.

Some additional history, via Seneca Creek greenway Trail: In 1784, Zachariah Maccubbin (MacKubbin) agreed to buy “Good Port,” as it was then known, from William Benson. Maccubbin failed to pay for the property so Benson had him dispossessed by ejectment. While Maccubbin had position, he tore down the decayed Benson’s mill on Good Port and built a new mill.

An Act to open “a road not exceeding thirty feet wide, from Barnsville to Zachariah Maccubbin’s Mill, and thence to intersect the Main Road leading from Frederick-Town (Frederick) to George-Town (Georgetown) at or near Log-Town (now Gaithersburg)” was passed Jan 25, 1806 by the General Assembly of Maryland. It is believed that this may be the current Barnesville Rd to Clopper Rd to West Diamond Ave, intersecting Rt. 355. In the Maryland Chancery Papers Index, there is mention of an injunction against Zachariah Maccubbin to keep him from removing timber from Good Port.

In 1812, Francis C. Clopper purchased Benson’s estate including the fairly new mill, which was built by Maccubbin sometime after 1784. Clopper rebuilt the mill in 1834. It was a grist mill and saw mill that was originally driven by an overshot wheel, but later converted to an undershot wheel. The mill was destroyed by fire in 1947 by an arsonist.

\

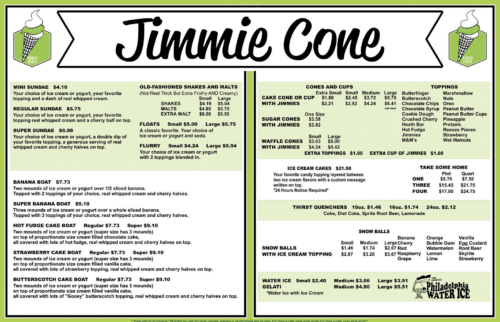

Today was a reminder that spring is around the corner. Another reminder for many who grew up in MoCo is that March 17th means Jimmie Cone opens for the season.

Jimmie Cone has been serving soft serve ice cream and frozen yogurt in Damascus since 1962, which make this year its 60th season! One of the reasons Jimmie Cone’s soft serve ice cream is loved by many could be because it is made with 10 percent butterfat, which is approximately twice as much as in McDonald’s and Dairy Queen soft serve. Cars usually pack the Damascus location on warmer days with long lines that move relatively quick.

Owners Dan and Bonnie Leiter bought Jimmie Cone in 1990 from Bill and Dorothy Harris, who are the son and daughter-in-law of the original owner. In 1997, Jimmie Cone opened its second location in nearby Mount Airy. The Mount Airy location is a bit larger than the original Jimmie Cone

The two locations, 26420 Ridge Road in Damascus and 1312 S Main Street in Mt Airy, both offer chocolate, vanilla, and twist every day. Strawberry, Black Raspberry and Orange flavors rotate weekly, and are also available twisted with vanilla. Frozen yogurt is also offered—one fat free and one fat and sugar free—changing weekly.

The menu can be seen below:

The annual Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day Tribute & Celebration will take place Friday, February 18 at the Music Center at Strathmore in Bethesda.

Montgomery County Executive Marc Elrich and the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Commemorative Committee invite you to the event, Ordinary People Doing Extraordinary Things for the Fight for Freedom, a tribute honoring the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Heroes of The Civil Rights Movement.

Ordinary People Doing Extraordinary Things for the Fight for Freedom will highlight the lives of celebrities and everyday people who supported Martin Luther King and the Civil Rights Movement. Learn how our Nation’s most celebrated superstars put their careers and lives on the line to fight for freedom and justice for all. Discover local civil rights participants who made significant contributions to the fight for justice in Montgomery County. This event will include musical performances and reenactments of celebrities such as Harry Belafonte, Joan Baez, Mahalia Jackson and more!

Researched and Written by Sharyn Duffin (Part 1 available here)

In Part 2 of African-American Education in Rockville, courtesy of Peerless Rockville, Sharyn Duffin looks at the desire for education and the establishment of black schools in Rockville and Montgomery County.

Desire for Education: Schools in Rockville

Congress enlarged the mission of the Freedmen’s Bureau in July 1866 to encourage and help finance efforts of freedmen, philanthropists, and states to engage in the education of blacks. The freedmen knew education was the path to economic and political independence that gave real meaning to their newfound freedom. Rutherford’s reports document advancements and challenges in establishing black schools in Rockville and Montgomery County. There was a school in Rockville as early as 1866. The Washington Evening Star reported on June 25 of that year that the teacher “was obliged to close the school on the 22nd owing to the inability of people to support it.”

The following month, Daniel Brogden and Solomon Williams appealed to the Freedmen’s Bureau for assistance in recovering from John Mortimer Kilgour funds they had collected and entrusted to him in 1858. The men argued that the money was “much needed by the Colored people to assist in securing a church and school.”

In October 1866, Rutherford reported a large school in operation at Sandy Spring, and “efforts are being made, with good prospects of success, for the establishment of a school in Rockville.”

To bolster these prospects, in February and March of 1867, twenty Rockville black men pledged to support a school by taking responsibility for money “as may be necessary to pay the board and washing [laundry] of the teacher and to provide fuel and lights for the Schoolhouse.”

Between the February 1867 petition and June 1867, a school operated in Rockville in the basement of the Methodist Episcopal Church. Rutherford noted that a Mr. Janney of the Baltimore Association for Moral and Educational Improvement of Colored People, who furnished the teacher, made “great objection” to it because it was “damp and ill suited to the purpose.” The church was the only large building accessible to the black community; hence the only place to house the school short of constructing one. Rutherford promised the Bureau’s assistance if the community decided to build one.

In July 1867, the Freedmen’s Bureau tracked down Kilgour, who had moved out of state. Some of the money, $18.50 (modern value about $300) was recovered and returned to the black community. The receipt for the return of the money was signed by Henson Norris and Hillary Carroll of the Rockville Colored School Board and witnessed by Daniel Brogdon and Solomon Williams.

Buoyed by the recovery of their meager funds and the promise of assistance from the Freedmen’s Bureau, school trustees purchased 1⁄2 acre of land on August 31, 1868 from a black woman named Mary Brashears for the sum of one dollar. The land was conveyed to school trustees “for the purpose of erecting, or allowing to be erected thereon, a School House, for the use, benefit, and education of the colored People of Montgomery County forever.”

The seven school trustees included four men who had signed the petition to support the school: William H. Kelley, Solomon Williams, William Baker, and Israel Butler. The other school trustees were Daniel and John Brogden, and Andrew Davis. Butler and Davis were younger than the rest of the trustees, and both were Civil War veterans.

The trustees informed the Freedmen’s Bureau that Israel Butler would collect the building materials. The location described on the deed places the lot about where the “Col’d School” is shown on the 1879 G.M. Hopkins Atlas map above. Most accounts say the school was built in 1876; however evidence strongly suggests the trustees constructed a school earlier.

A semi-annual report on schools for freedmen in 1870 quoted Daniel Brogden on his efforts to establish a school:

Daniel Brogden, once a slave, now eighty-two years of age, who bought himself “because he wanted a free hour to die in,” is now trustee of a colored school in Rockville, Maryland. Being asked if he had an education, “only what I got behind de plow-tail—stole it, like.” “How was that, uncle?” Why, when children gwine to school I goes up to de fence, git little lesson from dem in de book—give chile hen egg for it, you see.” In this way he learned to read his Bible. And the old man said: “If I git de school going in Rockville, I gwine to go and study, too.”

After public schools for black children were mandated in Maryland in 1872, existing colored schools were frequently incorporated into the school system.

In 1876, the Montgomery County Board of School Commissioners approved $600 to purchase a lot for a school in Rockville. William Veirs Bouic, who had successfully contested Mary Brashear’s ownership of the lot in 1870, sold it to them. The deed does not indicate the presence of a building.

It is clear that classes were held somewhere. There are records of payment to Ellen Watts for teaching from September 1869 to June 1870. Watts was listed as a teacher living in Rockville on the 1870 census. Moreover, on that census, at least thirty-three black children, many related to the signers, were recorded as attending school. The 1869 report by the Freedmen’s Bureau Supervisor of Education for Maryland lists 10 African American schools in Montgomery County, including Rockville.

To be continued.

By Mark Walston

Courtesy of the Bethesda Historical Society

Advances in transportation over the course of two centuries transformed Bethesda from a rural wayside stop into a bustling metropolis. But for much of its early existence, Bethesda was little more than “a wide spot in the road,” as one early resident put it.

That road (today’s Wisconsin Avenue and Old Georgetown Road) began in the far past as a ridgeline trail through ancient woods, carrying the first settlers, the Native Americans, as they hunted game in the land among the Potomac, Patuxent, and Monocacy Rivers. At the end of the 17th century it brought Dutch fur traders, who built a one-story granite trading post dominated by a great stone chimney rising up through the middle of the roof (part of which still stands) near the intersection of present-day River Road and Little Falls Parkway.

It also brought the English to newly granted plantations measured out of the virgin forests. In time, farmers hauled produce over the road, sacks of wheat and big, rolling hogsheads of tobacco destined for the nascent 18th-century port of Georgetown. Drovers herded livestock, British regiments marched in formation, and travelers joggled along the dirt road in wheeled wagons.

By the middle of the 18th century a small stone tavern had been built near a bend in the road, offering respite and replenishment to passersby. Situated near the northwest intersection of present-day Old Georgetown Road and Wisconsin Avenue, the “old stone tavern,” as it was familiarly called, was the first commercial establishment in the area—and the nucleus of what would become downtown Bethesda.

Bethesda’s early status as a wayside stop was commemorated in 1929 by the Daughters of the American Revolution, who erected their “Madonna of the Trail” statue honoring not those who stayed, but those who passed through. The 10-foot statue, sculpted by German-born artist August Leimbach and depicting a pioneer mother cradling a small child while another clings to her skirt, was one of 12 identical monuments placed along a route between Bethesda and Upland, Calif., commemorating women’s contributions to America’s westward movement. (Today, it seems as if the mother, her face set with a rugged determination, is leaning forward in nervous anticipation as she and her children prepare for the harrowing task of crossing Wisconsin Avenue at rush hour.)

By the early 19th century, the old road had fallen into disrepair, and in 1805, the Maryland legislature chartered a new company dedicated to improving the road between the District line and Rockville, the county seat. Work languished until the company was rechartered in 1817. Within a few years, the new turnpike opened, the first hard- surfaced road in the county, a 20-foot-wide strip veering off from the older Georgetown road near the stone tavern to run in a straight line to Rockville. The vision was to extend the pike to Frederick and beyond. A small, wooden tollbooth appeared south of the intersection, collecting fees from travelers—12½ cents for a score of sheep or hogs, 6¼ cents for every horse and rider, 25 cents for a coach or stage with two horses and four wheels—with the money divided among stockholders of the turnpike and, ostensibly, invested in the road’s maintenance.

Here and there near the new intersection, houses were built, modest affairs, simple clapboard homes of yeoman farmers fronting open fields of grazing cattle and rolling hills of wheat and corn.

In the 19th Century, Post Offices were frequently named for their postmasters or the establishments in which they were located. So when, in 1852, a Post Office was established in or near the local Presbyterian meeting house that still stands a couple of miles north of the intersection, high on a hill above the pike, it was called “Bethesda” after the meeting house, itself named for the miraculous Pool of Bethesda in Jerusalem. (To be fair, the area began to be known by that name not long after the church opened, in 1820). Not surprisingly, the church pastor was the first postmaster, but notwithstanding its ecclesiastical support the Post Office (though not the church) closed within six months.

Ten years later the federal government again deemed the area around the somnambulant crossroads sufficiently populated to warrant a post office, though this one was located closer to what we think of as downtown in William Darcy’s general store opposite the tollhouse. The Post Office, lackadaisically but not atypically, was named “Darcy’s Store.” When Darcy was relieved of his postmaster duties his successor, Robert Franck, yielded to the entreaties of the Bethesda church’s pastor (who apparently liked having the Post Office named after his congregation) and other citizens and successfully petitioned to rename it — and thus the area it served — Bethesda. The official date of the name change was Jan. 23, 1871, which we now denote the birthday of Bethesda. Today, the community is one of five so named in the United States.

Still, in the years following the Civil War, commerce in the village remained sparse. Progress had bypassed the crossroads community; the Metropolitan Branch of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, which began steaming through the county in 1873, ran far to the east. Farmers abandoned the toll road in favor of the railroad, a quicker and easier means of transporting goods to the Washington markets. Travelers, as well, could now reach downtown D.C. in a matter of minutes by rail, with greater comfort than over the rutted pike. The old road declined in importance and slid into disrepair, and the village languished. By 1878, the time of its earliest enumeration, its population numbered only 20. There was the lawyer, Joseph Bradley, and a doctor, James H. Davidson; two blacksmiths, William Kirby and William Lochte, whose shop stood at the northwest corner of the pike and the Georgetown road. Benedict Beckwith was the community’s carpenter, while James Austin served as carriage maker. R.C. Lester had taken over the storekeeping duties, doubling as postmaster.

Then, in the last decade of the 19th century, two occurrences radically altered Bethesda’s future. By 1890, the newly formed Chevy Chase Land Company had begun to amass property to the east of Bethesda, with the intent of creating a new sylvan enclave for Washington’s social and political elite. And the following year, 1891, the trolley arrived, the electric railroad tootling up the pike, then veering left to stay on the ridgeline and avoid the hills. In other words, it followed the original path, which we correctly — but unoriginally — now call Old Georgetown Road. Bethesda area farmers now had their own means of carrying produce into the city. Urban dwellers found a way to escape to fresh, clean country air. And enterprising businessmen found an entree to carving even more suburban subdivisions out of rail-adjacent real estate.

The trolley’s original terminus was Alta Vista, on the west side of Old Georgetown Rd. just north of Cedar Lane, where the railway company built an amusement park as an incentive for evening and weekend riders. Opened in 1891, Bethesda Park quickly became one of D.C.’s most popular entertainment spots, complete with roller coasters, Ferris wheel, bowling alleys, shooting galleries, a concert and dance hall and a hotel. Patrons were treated to performances by Wichita Jack’s Wild West show, Professor Hampton’s dog circus, “Prince Leo, King of the Tight Rope Walkers” and other astonishing acts of the day. A hurricane decimated the park in 1896. It would never reopen. Thankfully, the trolley remained.

By 1900, the trolley line had been extended to Rockville—and none too soon, because the old turnpike had descended into a dismal state, and the company had declared bankruptcy. An 1899 report called it “one of the worst pieces of main highway in the state.” In 1908, with the creation of the State Highway Administration, the old pike would be absorbed into the state system and modernized with a new hard-packed surface. “It is now considered to be the only good road between the district and the upper part of Montgomery County,” The Washington Post reported.

The trolley proved a boon to the village’s development, as did the covenants of neighboring Chevy Chase, which prohibited commercial establishments within the residential area. The new suburbanites needed a place to shop, and Bethesda would become that place. The first merchant to capitalize was Alfred Wilson, who, in 1890, built his new general store on the site of the old tollhouse, a few hundred feet south of the intersection of the pike and the old Georgetown road. It quickly became the center of community life, serving as the post office, the polling place and, in 1921, the village’s first library. The structure still stands, the oldest building in town and the only reminder of the community’s 19th-century crossroads beginning. (In 2017, to make way for a new office building above the Bethesda Metro stop, it was moved a few blocks to Middleton Lane, between the Bethesda Theatre and Pumphrey Funeral Home on the east side of Wisconsin Avenue).

In 1910, the Georgetown Branch of the B&O Railroad arrived, running through town on its way from Silver Spring into the District. The freight-only line brought new commercial growth along the tracks, with coal yards, lumber yards, a planing mill, an ice plant and more loading and off-loading at the Bethesda station, perched west of Wisconsin Avenue in an area called Miller’s Flats that ultimately became the site of Bethesda Row.

Despite the industrial growth, a rural quality prevailed in the village. Horses grazed in empty lots, and sheep and cattle roamed the fields on either side of Wisconsin Avenue. But soon a revolutionary presence arrived on the road—the automobile. Industrialist Henry Ford had introduced his affordably priced Model T in 1908, and in the first year of production more than 10,000 were sold. By 1926, nearly 15 million Fords were rolling down America’s streets and engendering the rise of the new automobile suburbs.

The trolley had jump-started growth, but the auto threw it into high gear. All around the village center suburban communities rose, vying with one another as they promised luxurious homes in beautifully landscaped surroundings just a short car trip to and from downtown D.C. offices. Early subdivisions such as Drummond, Bradley Hills, Battery Park, Kenwood and Leland competed for a rising upper-middle class of home seekers, noting in their advertisements that “adequate and proper restrictions will be placed in the deeds” to insure “a high character of development.”

In 1912, local real estate magnate Walter E. Tuckerman purchased 185 acres at the southwest corner of the pike and the old Georgetown road, carved it into 250 lots and created a community for “those of refined taste, demanding a better social atmosphere than surrounds the usual suburb, a more picturesque environment for an all-year-round home out of the city, without the expense and responsibility of a large estate.” His gated community, originally called Edgewood but renamed Edgemoor in 1916 to avoid confusion with another Maryland community and military installation of that name, provided all the modern amenities, including “pure artesian water, sanitary sewage, gas for cooking, heating and lighting, electric light and telephone service.”

Gracing the center of the community was a large green expanse reserved as a sports complex for residents. By 1920, two tennis courts had been built in the open field, with a small grandstand shaded by a broad awning. A clubhouse, swimming pool, bowling and putting greens soon followed. The Edgemoor Club, still operating on Exeter Road, would reach acclaim in the late 1950s when Pauline Betz Addie—ranked No. 1 in the world in 1946 and winner of six Grand Slam tennis titles, including Wimbledon, and Forest Hills four times—became the club pro.

Exclusive sports and social clubs soon became a trademark of Bethesda living. The older Chevy Chase Club, originally formed in 1892 as a hunt club, and the Columbia Country Club, which moved to its present location in 1910 and hosted golf’s U.S. Open in 1921, were soon joined by an array of others, forming a wide green ring around the village. The Montgomery Country Club was established in 1913 along the trolley line operated by the Washington and Great Falls Railway and Power Company, following a route that is now Bradley Boulevard. It was soon joined by the Town and Country Club, founded by members of Washington’s German-Jewish community. That club moved to the northern boundary of Bethesda in 1921 and became informally known as “Woodmont” for the subdivision immediately to its south, a name that became official in 1930. Out River Road, Congressional Country Club, catering to the political elite, opened in 1924, as did Burning Tree Country Club, an exclusively male bastion. Kenwood Golf and Country Club followed in 1928, and one year later the Montgomery Country Club would be converted into the National Women’s Country Club. “Men are experiencing the women’s revenge,” The Washington Post reported. “Women have a club of their own now—one of the finest nine-hole courses in the country.” In 1947, the property was renamed again and became Bethesda Country Club.

Bethesda’s commercial district responded to the suburban influx with equal gusto. In 1925, the Bank of Bethesda – also founded by Tuckerman, and originally housed in the gatehouse that marked the entrance to Edgemoor — tore down Lochte’s old blacksmith shop, which for half a century had stood on the northwest corner of the old Georgetown road and the pike (now rechristened Wisconsin Avenue). In its stead, the bank erected a handsome new stone headquarters, a building that, today dwarfed by its towering neighbors, served for many years as a branch of SunTrust Bank and still anchors the corner.

Farther down the avenue, residential developers and brothers Monroe and Robert Bates Warren would unveil an entirely new breed of commercial building: the shopping center. Completed in 1927, the picturesque, Tudor-style Leland Shopping Center offered an unbroken row of stores stretching south of the eastern corner of Leland and Wisconsin. Residents of adjacent communities could now enjoy a stroll along the avenue, eyeing wares neatly posed in the center’s display windows. Across the street, local developer George Sacks would open his own stone-fronted shopping center, with angled parking conveniently located out front and apartments on the second floor. The northern end featured Northwest Ford’s sparkling auto showroom. More than 80 years later, the two centers still cater to Bethesda shoppers.

Business was bustling in the 1920s, as was the traffic through the village center—so much so that, on July 8, 1930, the village’s first traffic signal appeared, installed at the intersection of Wisconsin, Old Georgetown and the newly completed East West Highway. A State Highway Administration 10-hour traffic count at the intersection in 1930 recorded 6,000 vehicles traveling along East West and Old Georgetown, and 8,000 vehicles on Wisconsin, making it the busiest intersection in the county. (By comparison, Wisconsin Avenue in 2010 had a daily average traffic count of more than 62,000 vehicles.)

The American economy rolled along with astonishing speed in the Roaring ’20s; fortunes were quickly made in stock and land speculation, and “a nice home in the suburbs” became de rigueur for the nouveau riche. Within a 10-year period, from 1920 to 1930, the population of Bethesda soared from 4,800 to 12,000, representing 30 percent of Montgomery County’s total population. Even the onset of the Great Depression in 1929 couldn’t dampen the explosive growth. The large number of government paychecks invested in home mortgages, filling the coffers of area banks and supporting local businesses, helped insulate Bethesda from the severe economic conditions ravaging the rest of the nation. County farmers banked on the village’s financial strength with the establishment of The Farm Women’s Cooperative Market in 1932, a self-help project selling locally grown produce out of a tent along Wisconsin Avenue. Later that year, the farm women would build a permanent market house on the east side of Wisconsin that has been in use ever since.

Stimulus money injected into the U.S. economy by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs would bring new additions to the avenue’s streetscape. In 1938, under the auspices of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a new, classically inspired post office was built on Wisconsin Avenue. The Colonial Revival building – like the Bank of Bethesda, the C&P Telephone Building, and several others — was constructed out of native stone trucked in from the Stoneyhurst Quarries out River Road. It served as a Post Office until 2012, and is now a yoga and fitness studio.

Then came two ambitious government projects that would have a monumental impact in shaping the community. In 1938, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) began development of its new research complex at the village’s northern end. Adjacent property owners, as well as the Bethesda Chamber of Commerce, were leery. The NIH campus would change the atmosphere of the neighborhood, they argued. It would be unhealthy for residents if the government were allowed to study infectious diseases so close to homes. But then Roosevelt visited the proposed campus and gave it his hearty approval.

While touring the property, FDR looked out over Rockville Pike, remarked on the bucolic Bethesda environs, and pointed out land he thought would be perfect for a proposed Naval Medical Hospital. The next year, builders broke ground on a soaring, 20-story steel-frame and reinforced concrete building designed by master French-American architect Paul Philippe Cret, who worked from a sketch by FDR himself that was inspired by the tower of the Nebraska State Capitol in Lincoln. At its completion in 1942, the Naval Medical Center, along with the NIH, would not only set a northern limit to the expansion of Bethesda’s commercial district, but would eventually bring thousands of new workers to the area’s busy streets—and thousands of new homeowners to the exploding suburban communities.

A few years earlier, entrepreneur Sidney Lust believed the growing prestige of Bethesda justified the building of a high-style, major modern theater, and he hired the noted architect John Eberson— designer of Silver Spring’s Silver Theatre, today home to the American Film Institute—to design a lively art deco facility. At its opening in 1938, local papers hailed the Lust theater — then called the Boro, soon renamed the Bethesda Theatre, and today known as the Bethesda Blues & Jazz Supper Club — as “a triumph in modern theatre construction,” and messages of congratulations poured in from such Hollywood personalities as Clark Gable, Gary Cooper, Spencer Tracy, Shirley Temple and W.C. Fields. The sumptuous interior included a “streamlined lobby painted in modern designs” with mirrors, display cases, an elaborate coved ceiling and indirect lighting. Off the domed foyer were “beautifully appointed” smoking rooms and lounges, and the stage was described by the Bethesda-Chevy Chase Tribune as “the largest in the suburban area and equipped to handle presentation acts.” The building further distinguished itself as one of the first in town to offer central air conditioning.

Moviegoers could grab a quick preshow meal at Bethesda’s new Little Tavern outlet, opened in 1939. Little Tavern was an early hamburger chain that promised “Cold Drinks, Good Coffee,” and urged patrons to “Buy ’em by the bag.” Founded in 1927 by Harry F. Duncan, the chain competed with other pioneering fast-food enterprises such as White Tower and White Castle, each of which had created a distinctive style of architecture to advertise their wares. The Little Tavern chain adopted the “Old English” style of a quaint, pitched-roof roadside eatery, yet constructed of such modern and reputedly more sanitary materials as Vitrolite, tile, Formica and aluminum alloys. (The building survives, and today is home to the Golden House Chinese restaurant at the intersection of Wisconsin and Cordell avenues.)

Between 1930 and 1940, Bethesda’s population more than doubled to 26,000. But all was not well in boomtown. Residents were becoming concerned about the haphazard appearance of their new commercial district. Fast-paced but fragmented development after World War I had left the village with a patchwork look, which some felt unbefitting its new status in the county. As one community leader noted in 1939, despite the fact that Bethesda was on its way to becoming the county’s major retail trade center, “in growing, it has developed a hodgepodge of conglomerated architecture in which brand new stores adjoin age-old frame houses, and the large and the small, the brick and the frame, the stone and the stucco are jumbled together.” Despite their plea for architectural quality, civic leaders had little control over what was built, and how the new shops and offices contributed to the expanding streetscape.

After World War II, as the nation headed into the halcyon days of the 1950s, the residential and commercial boom continued with vigor. But geographical restrictions—the circling of the business district by stable residential communities, country clubs and federal lands—worked to contain the downtown’s outward expansion. Development was forced upward, and by the 1960s, eight-, nine- and 10-story office buildings had begun to cast longer shadows on Wisconsin Avenue. The East Tower of the Air Rights Building on Wisconsin Avenue, completed in 1964, was one of the downtown’s first 10-story high-rises. Gradually, many older retail businesses were demolished in the face of ever-rising rents and land values. Local and national stores alike began to retreat to the new, sprawling outer-suburbia shopping centers that were starting to dominate the area’s retail scene. Wheaton Plaza, whose plans were laid in 1954, would offer consumers a wonderland experience, with covered walkways, major department stores and rows of specialty shops. It would become the first regional mall in the Washington area and, by 1963, the fourth largest in the United States. Then, in 1968, Montgomery Mall would take shopping to even greater heights as the area’s first totally enclosed, all-weather mall, further luring major retailers away from possible downtown Bethesda locations.

Meanwhile, the continuing patchwork nature of the downtown area continued to present a built environment with no distinguishable character of its own. John Westbrook, former head of the urban design division of the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, recalled in the 1980s the Bethesda he first encountered in the early 1970s. “The central business area had no heart,” Westbrook said, “no sense of identity, exposed parking, concrete buildings mushrooming out of asphalt, no trees, no greenery. What was there was dying in the median strips.” Soon, however, the county would step in and attempt to control the architectural quality of any new construction—and bring a sense of place to the downtown area.

With the selection in 1972 of the Wisconsin Avenue and Old Georgetown Road intersection as the site of the Bethesda Metro subway station, a rush of new development in the downtown was inevitable. Again, the progress of transportation—from turnpike to trolley to automobile to subway—seemed destined to direct the town’s future. That sparked residents’ fears that Metro’s arrival would trigger even greater unregulated development, so the county government adopted a master plan in 1976. Citizens and planners agreed that the only options were spreading new construction throughout the district or concentrating it at one point. What the planning board eventually recommended was a pyramidal development scheme for downtown Bethesda, with the tallest buildings massed around a Metro station “core.” As buildings moved away from the town center, height limits would be reduced, stepping down to a scale more in keeping with that of the surrounding residential communities. Additional buffers between homes and offices were to be provided by interposed parks, playgrounds and public buildings.

In 1984, Bethesda’s Metro station opened—one year after the county had approved plans for 14 medium- to high-density buildings surrounding it in a package redevelopment plan unprecedented in the county’s history. When completed, the mélange of post-modernist architecture would add 3.1 million square feet of new commercial and residential space to Bethesda’s 9 million square feet of commercial space, with an estimated 13,000 to 15,000 new employees filling the office towers.

Though interrupted by the recession in 2008-10, the redevelopment of downtown Bethesda proceeds apace, with numerous office builds, apartments and condominiums completed over the past decade. Highlights of the past 25 years include the development of the Bethesda Row mixed use complex in the late 1990’s, and the transformation of the Woodmont Triangle. Once the “other side of the tracks” in Bethesda, today it is home to scores of restaurants and over a dozen high rise apartments/condos. For the past decade growth has accelerated in recognition of the fact that downtown Bethesda will be the western anchor of the Purple Line as well as the new headquarters of Marriott International, which is relocating from Democracy Blvd a few miles north.

We are a long way from the wide spot in the road.